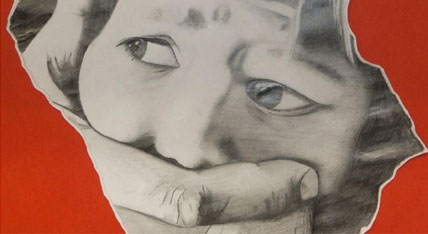

How Iris was Captured

Radio interview with a woman who was trafficked for sexual exploitation.

read more

Children as young as seven are performing backbreaking labour on Zimbabwe’s sugarcane plantations, all for just $1 a week in pay. Tapiwa (not his real name), is one such boy who has been working in the fields for the past six months. His parents died in 2017, prompting him to find some form of income to feed himself and his elderly grandmother. “I’ve never been to school. This is all I do,” he told the Guardian. “I am helping my grandmother. If I don’t do it, we will die of hunger. My grandmother does not want me to go hungry, so she encourages me to work. It is tough, I get sick sometimes.”

The Guardian reports:

Tapiwa is joined in this “maricho” (menial work) by his grandmother. They both earn $2 (£1.5) every fortnight.

This goes towards buying food and soap. “I would want to go to school one day so that I [can] buy my grandmother what she wants,” Tapiwa says.

This is life for the poorest young boys at the plantations. Mukwasine farmers have been criticised for underpaying labourers who constitute a critical part of the sugarcane industry in Zimbabwe. In cane cutting season, local farmers want cheap, casual labour.

During school holidays the young labourers work in the cane fields for a meagre $10 per month.

“If I need schools fees, I have to go for maricho,” says one. “Our parents cannot afford books and other things we need for school so we have to work hard.”

Children like Tapiwa work in the sugarcane fields without protective clothing, meaning they are exposed to diseases and snakes.

The government of Zimbabwe has threatened to investigate the sugarcane industry for abuses. Back in May of this year, the country ratified the protocol of 2014 to the Forced Labour Convention, signalling to push to root out the problem.

“We are worried. The ministry is concerned with such a development because we are signatories on the conventions on the rights of the child,” explained labour and social welfare minister Sekai Nzenza.

“We also have a programme which we are running to end child labour. We will do as a matter of urgency an investigation into the case to ensure the protection of these children.”

According to the US Department of Labour, dangerous child labour persists in Zimbabwe’s agriculture and mining sectors, pointing to the deterioration in the economy as a driver of the problem, as well as lack of access to basic schooling.

(The Guardian 19 Nov. 2019- cited in Freedom United).